Hollywood Maverick 101: How to Stay Relevant for 40 Years

Hi, it’s Thomas Cruise Mapother IV—because, apparently, “Tom Cruise” just wasn’t flashy enough even for Hollywood’s pint-sized action hero. This 62-year-old American star has spent decades honing the art of asking us to pretend not to notice that their guy requires a phone book in order to look over wheels when he’s driving. And we’re all probably guilty of this nice fiction.

His awards room is probably one of those participation prize dreams: an Honorary Palme d’Or, right at eye level, exactly three Golden Globes, and four Academy Award nominations always and always just out of one’s reach–just like all things over five-foot-seven. His movies, ridiculously, have generated more than $13.3 billion overall, and we all know that it’s far more insignificant to be humongous than it is to be able to sprint very, very quickly and always be scowling that, oh dear, something, er, is exploding behind us.

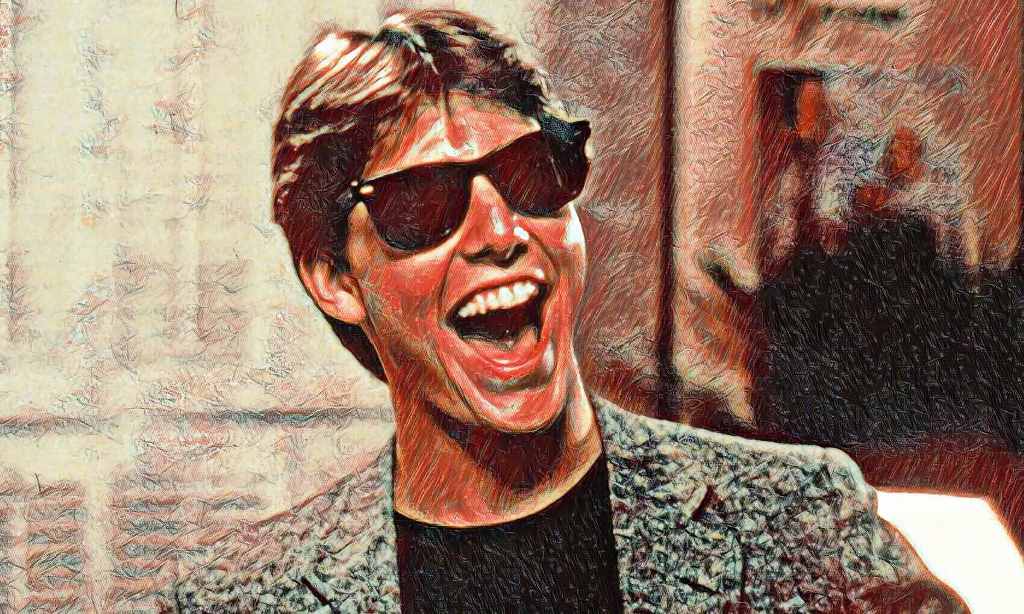

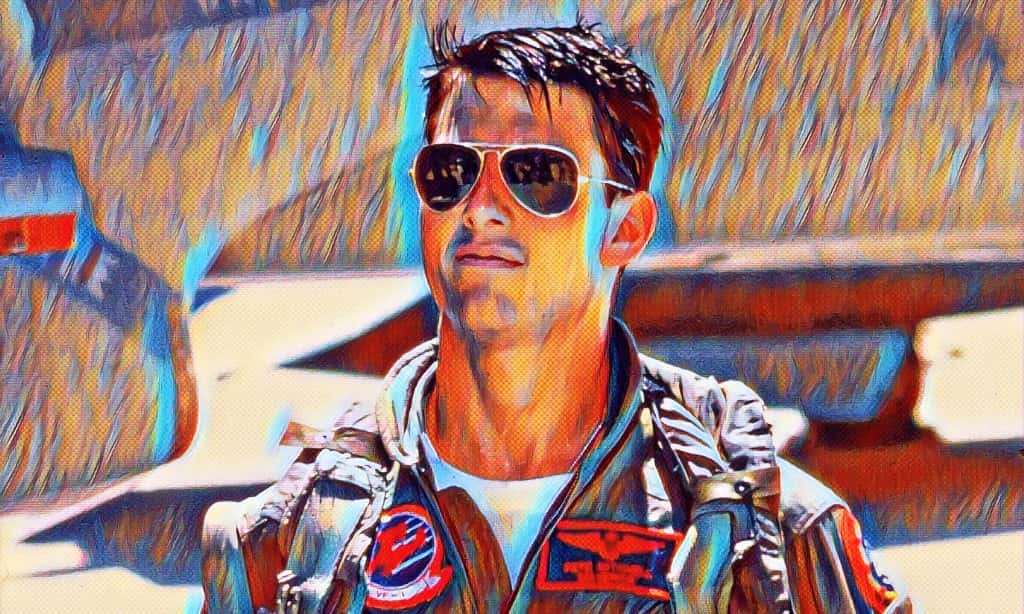

Tom’s profession as an actor started in the early 1980s in the midst of what must be Hollywood’s finest era of strategic overcompensation. “Risky Business” in 1983 produced what must be characterized as a thousand underpants dancing satires, but “Top Gun” in 1986, at last, placed our vertically-challenged joe in sex symbol range. There’s nothing that shouts “irresistible pilot” as the man who most assuredly needs special cockpit provisions, but wins out nonetheless by sheer dental wizardry and only one or two more than charm.

The later 1980s also included Tom’s “serious actor” period, that all action heroes must demonstrate that they can stitch together between the pyrotechnics. “Rain Man” and “Born on the Fourth of July” demonstrated that he was capable of doing serious work, the latter winning him a Golden Globe for being so luminous as Ron Kovic one forgot he was acting—ability that would serve him well later, illustrating Scientology to bewildered journalists.

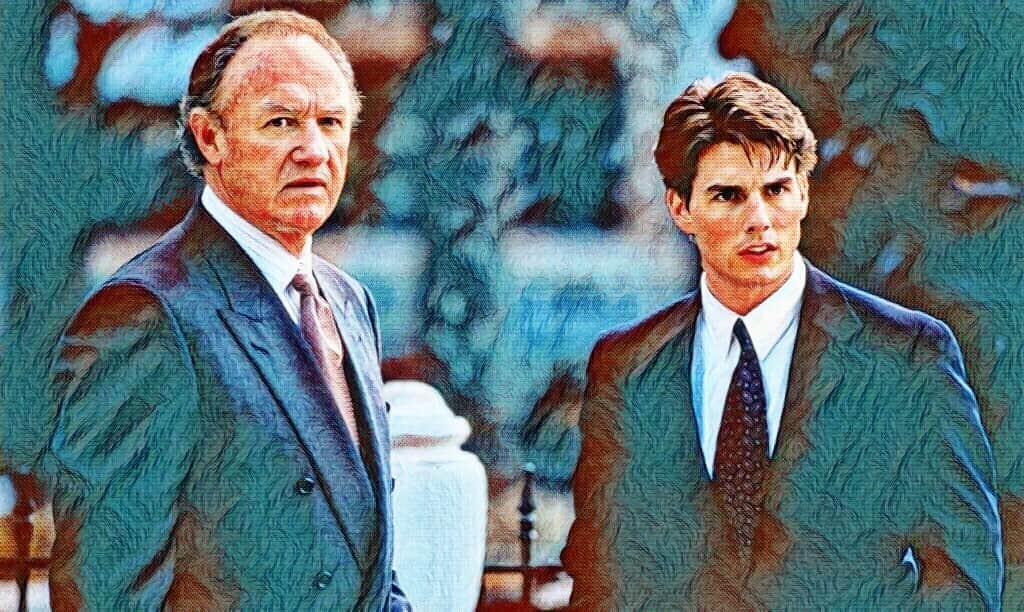

The 1990s arrived, and Tom had his do-everything period as heartthrob. “A Few Good Men” had him being outwitted intellectually by Jack Nicholson, who appeared to steal each scene through metaphorically and literally glowering over Tom and still. “Interview with the Vampire” appeared particularly decadent–to be able to observe the pint-sized hero behave like an undead creature of darkness while appearing like he could be knocked over by an awfully unruly butterfly. “Jerry Maguire” treated us to “Show me the money!”, the unofficial Tom life motto, considering his stratospheric pay demands through and through for essentially running around exotic settings.

The crown, though, still belongs to the “Mission: Impossible” franchise—eight movies of Tom Cruise suspending himself, more and more ludicrously high up, thumbing his nose at physics, common sense, and general workplace safety regulations. The self-proclaimed man who can’t reach the cereal aisles has managed to sell the international audience on being able to ascend Dubai’s Burj Khalifa and surf planes like surfboards. It’s either the greatest acting feat in the history of cinema or the longest-playing short-man complex on tape, period.

All stunts grow that much more edge-of-his-seat-death-defying, apparently, because Tom himself isn’t quite fond of green screen and CGI one whit. “Computer-generated images? I’ll just hang off this helicopter with my bare hands, thank you very much!” His Guinness World Record title for movies with the most $100-million openings streak is basically “movies where Tom Cruise runs around like a headless chicken while just barely frazzled”—and those little legs zip about like high-octane hummingbird flaps propelling him through flames and away from questions about his religious rituals.

And Scientology—Tom’s “support” of L. Ron Hubbard’s science fiction lends credibility to his stories in his films. His Oprah-bullying, couch-jumping, “I know the history of psychiatry!” tantrum was internet gold. Seeing the man deliver lectures on alien overlords with the same seriousness that he delivers on diffusing imaginary bombs was peak unintentional comedy.

The man has a pilot’s license, and that makes perfect sense and utter nonsense. Tom, of course, had to learn how to fly—possibly just to experiment mid-air himself with stunts. The image of him needing booster seats in order to reach control panels, though, remains irresistibly humorous.

At 62, Tom Cruise is Tinseltown’s biggest bankable enigma, living proof that raw willpower, better dental hygiene, and human’s general need to suspend disbelief in oneself can bridge any vertical disadvantage. He’s been People’s Sexiest Man, received army commendations for dress-up soldier, and still risks life and limb on our behalf. In an era of CGI stand-ins and green-screened whatever, Tom Cruise is stubbornly, by nature, analog—one-man action figure in pocket size who refuses to be swayed from the notion that gravity exists and it’s got him in its crosshairs.

From 15 Schools to Superstar: A Chaotic Childhood Story

Prior to the death-defying, ageless wonder star persona of Tom Cruise in Hollywood, there was only Thomas Cruise Mapother IV, so forgettable a name that even fate needed a face-lift. A spindly, wide-eyed Canadian immigrant, a makeover awaited him in the most unlikely of places: a fourth-grade classroom in Ottawa, where liquid gold nectar falls and dreams are born of circumstance.

Image of 1971: the Mapother family rolls into Canada like some tawdry American Dream. Dad—Thomas “The Destroyer of Family Dinner” Mapother III—had won a contract performing defense work on a subcontract with the Canadian Armed Forces. Irony, mind you, because his own son would one day call him a “bully” and “a coward.” Nothing says military genius like inking a contractor whose mediative talents apparently reached their zenith scaring nine-year-olds.

They wound up on Beacon Hill like some insane sitcom no one asked for. Little Tommy, too small even to peek over his desk, wound up at Robert Hopkins Public, where fate awaited in the guise of a drama teacher, one George Steinburg. Under Steinburg’s reluctant guidance, wee Tommy gathered with six other lads and tumbled into the biggest of elementary school stage prophecies ever: some random play by its name of “IT.”

Really, though, “IT”—the same mysterious energy that Tom’s been pursuing ever since, dodging impossibly grim situations, narrowly escaping from helicopters, or making us believe there’s a fountain of youth deep within some corner of his Malibu lair.

The play took place at the Carleton Elementary School drama festival, where festival co-ordinator Val Wright was bracing herself for the typical fourth-grade disaster of forgotten lines and backwards costumes. What she witnessed, instead, was what she’d later refer to as “excellent movement and improvisation. a classic ensemble piece.” Translation: nine-year-old Tom Cruise was doing his own stunts and method-acting at recess.

But Canada gave Tom something more than the dramatic wake-up call—it gave him a survival manual of the nomad. The Mapother family motto: “Why put down roots when you can collect moving boxes?” By his sixth grade, he’d switched to Henry Munro Middle School, one of the stops in a childhood odyssey that would see him attend fifteen schools in fourteen years. You learn your times tables, Tom learned life is a Grand Guignol of make-it-up-as-you-go-along theater where your next line—and your next address—are perpetual mysteries.

This constantly changing world created a perfect storm of potential fame. Every move required adaptability. Every potential school required rebuilding. Every dinner with sweet old dad contained as much emotional material as a thousand on-screen meltdown endings. Tom, in turn, performed a PhD on the strength of the human spirit while other kids were mastering finer points of the long division.

The Canadian half of Tom’s existence ended on the big screen when his mother, Mary Lee, had had enough of the “merchant of chaos.” In a scene swiped straight from every Lifetime original movie ever produced, she rounded up Tom and his three sisters—Lee Anne, Marian, and Cass—and staged a histrionic escape onto American soil. One can only wonder at the dialogue: “Children, we’re escaping your father’s defense consulting firm and off to the land of dreams and men who do not treat their family like they would the enemy.”

With benefits of hindsight, those Ottawa years are idealized opportunities. Being forced on the move all the time aided one in staying nimble. Having a non-functional family system offered emotional material for later acting projects. Who can forget, too, that grade-school acting course? It sewed the seed whose fruit would be one of Tinseltown’s better-known faces—one which has become impossibly locked in a time warp since, say, the Reagan era.

It’s almost poetic. Tom Cruise discovered his calling in the land of universal health care and hyper-politeness, courtesy of a drama teacher who probably thought he was merely running a high school after-school program. Their dads had no idea they were in the presence of a legend in waiting, a man who would one day convince audiences on television that the answer to life was running, very, very fast, and voluntarily jumping out of airplanes was a normal day in the office.

The irony is tasty. Canada—that humble, laid-back country—unconscious of itself, provided Holly-wood with its all-time perfect action hero. We got Tom’s thunder-jolting wake-up call, survival senses, and seemingly wizard-like aging habit. For all such brilliant misunderstanding, we are forever indebted. Who would ever think between hockey arenas and Tim Hortons, a future legend was honing flight?

Tom Cruise’s Acting Career

1980s: From Busboy to Box Office: Tom Cruise’s Wild Rise to Fame

Tom Cruise – the actor who assured the studio that height is an issue of attitude and a very, very quick sprint is an appropriate acting technique. Early c.v. is a masterclass in brashness as a tool, a reminder the biggest improbabilities of all take only illmitable self-belief and a zero respect for mathematical possibility.

Sees Cruise, 18 and bursting onto New York City, with the calculating swagger of an over-caffeinated squirrel. Armed with a mother’s blessing and what can otherwise be called industrial-strength optimism, the man set about taking his mark on the city of entertainment with all the acting chops of a second-string high school drama club second banana. First acting gig? Busboy – because nothing screams “future action star” like learning the finer ins and outs of wiping down one’s fellow people’s tables. The poetry gets almost claustrophobic: a man who would go on to clean up Hollywood’s spills in life started by mopping up actual spills.

But our vertically impaired hero was not satisfied with New York’s unambitious potential. He stuffed his ambitions into one of whatever duffel bag was available and bought a one-way ticket to Los Angeles, the sun-baked desertscape where thwarted ambitions are fuel for Botoxed brow creases. Having signed with CAA – supposedly in order that some one might officially declare a height disadvantage – he launched a blanket blitz of a business that dealt in headliners who did not need apple crates on love classics’ breasts.

His first on-screen time in 1981’s “Endless Love” expired as quickly as a microwave dinner cycle, but a couple of months later “Taps” provided him with his career-defining moment, one which would be the signature of his whole career game plan. In background faces, Cruise impressed director Harold Becker enough to move from mere cosmetic background to speaking wallpaper. One hopes there is dialogue: “The little kid exudes such intense focus that we should have given him actual dialogue before he hums his way through the camera lens.”

And then 1983 arrived like Christmas morning for all would-be heartthrobs of the world. Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Outsiders” landed Cruise in the company of that sort of testosterone-fueled group cast that made adolescent girls remake their bedroom wall posters. Matt Dillon, Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, Patrick Swayze – basically a lineup of 1980s concepts of male attractiveness, and yet our little hero hung out with this teen angst giants without the aid of a stepladder.

But 1983 still had some left in the tank to continue handing out career-defining moments. “All the Right Moves” was prescient in its title, and “Risky Business” Became the cultural phenomenon which taught America a universal rule: you can be concise, slightly manic, and yet irresistibly charming as long as you’re gliding around hardwood floors in one’s undergarments and Bob Seger is blaring in the background. Who would have anticipated interpretive dance in tighty whities as a valid audition technique?

1986 delivered “Top Gun,” where Cruise starred as a pilot even though he was almost too short not to need a boost to peer down cockpit panels. This nerve – the guy didn’t give a hoot about physics, considering it a recommendation, not a requirement. Having flown high, he co-starred in Martin Scorsese’s “The Color of Money,” rebelliously alongside Paul Newman, one of those types who had been cool as a capital “C” ever since Cruise twinkled in the gaze of the eye of our nation’s capital’s Scientology-obsessed teens. Referring to both actors as appearing like “genuinely top-notch pool hustlers” in a piece, The Washington Post seemed happily oblivious they were gazing upon the beginning of the gentleman who would much later make dodging explosions a career.

“Cocktail” in 1988 demonstrated box office and critical success are planets apart. The film raked in enough cash to briefly astonish bystanders who were blind to its dizzying badness, and Cruise’s performance had become so irretrievably suspect that it earned him a Razzie nomination for Worst Actor – an honor reserved for genuine commitment to dubious decisions. Fortunately, “Rain Man” later that year reminded everyone there was an actual actor somewhere under the manic fervor and gravity-defying eccentricity.

But “Born on the Fourth of July” in 1989 was Cruise’s all-time “hold my protein shake and watch this” scene. Roger Ebert, who did not hand out undeserved praise, produced what amounted to a love letter: “Nothing Cruise has done will prepare you for what he does in Born on the Fourth of July.His performance is so good that the movie lives through it.” Overnight, the New York busboy had become Golden Globe winning,Academy Award nominated, genuine dramatic presence.

From extra! background to Best Actor nomination, the early career path of Cruise defies! all rational expectation of the Tinseltown dynamics of stardom.! Proving, reminding us, that maybe the greatest improbability of! success can be! achieved on! nothing less than sheer refusal to! respect!! one’s! boundaries – a credo! that later came! in handy when one day he!! opted! for death!

-defying stunts on location as! a real! career booster.

1990s: Drama roles

The 1990s: when Tom Cruise set out on a crusade to demonstrate there was more than a pretty face who could run in slow motion. Twist: we can be sure he demonstrated a point so conclusively, the remainder of Tinseltown took early retirement.

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room—having your wife appear in not one, but two of your films. Nicole Kidman played Cruise’s love interest in both Days of Thunder (1990) and Far and Away (1992), because apparently the pool of actors in those Holywoods were so lacking they had to search around the family moat. And, of course, business with pleasure somehow brought box office returns and not divorce court. Who would’ve guessed nepotism could be so profitable?

And then there was The Firm, where Cruise starred as a lawyer—because there’s nothing that better puts “dramatic range” to the test than seeing America’s all-time leading man of action scowling at briefs. Critics gobbled up the movie like complimentary donuts at the precinct, and box office ticket receipts could’ve financed a few small countries. Apparently, placing Tom Cruise in a suit was a discovery of fire, only with higher rates of profit.

This is where things become tastefully insane. Way back in 1994, our golden boy took a bite out of Interview with the Vampire with Brad Pitt, Antonio Banderas, and Christian Slater. When book author Anne Rice heard of this acting decision, a veggie who attended a BBQ seminar would be equally happy. She had their hopes, of course, set on a brooding type by the name of Julian Sands—you know, the one who would be asked to brood in a Gothic keep and dazzle with thuggish European panache. But no, what does she get instead? Tom Cruise, who had all menace of a golden retriever.

M. Night Shyamalan-style shock: Rice had viewed the film and loved it, she laid out a whopping $7,740 (equivalent to $16,420 today) for a two-page ad in Daily Variety basically stating, “Oops, my mistake, Tom. You are absolutely brilliant.” In effect, the woman spent top ad rates publicly eating crow off the back of a mariachi band. That is not final vindication, what’s next?

The mid-90s saw Mission: Impossible, in which Cruise starred as superspy Ethan Hunt—an actor so ideal cast on the basis of his “breathlessly gung-ho screen personality” one couldn’t help star at him like a key recognizes its lock, even when, of course, one can’t hang keys from helicopters and pull death-defiance. Brian De Palma directed said testosterone-fuelled classic, and there’s enough sequel-ing to stock a fast food chain. Clearly, seeing Tom Cruise risk life and limb on our behalf gets old, ever.

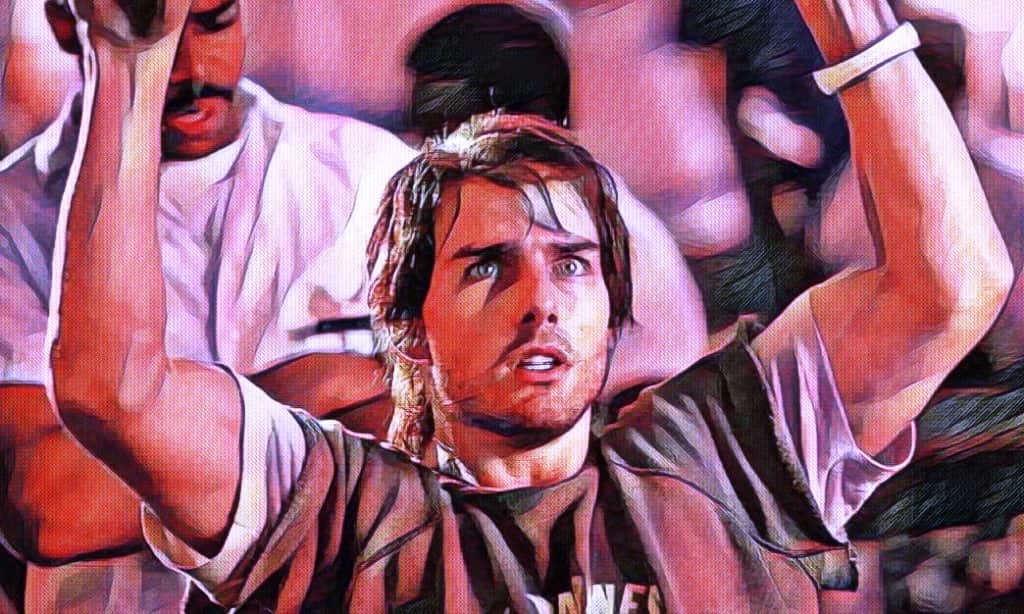

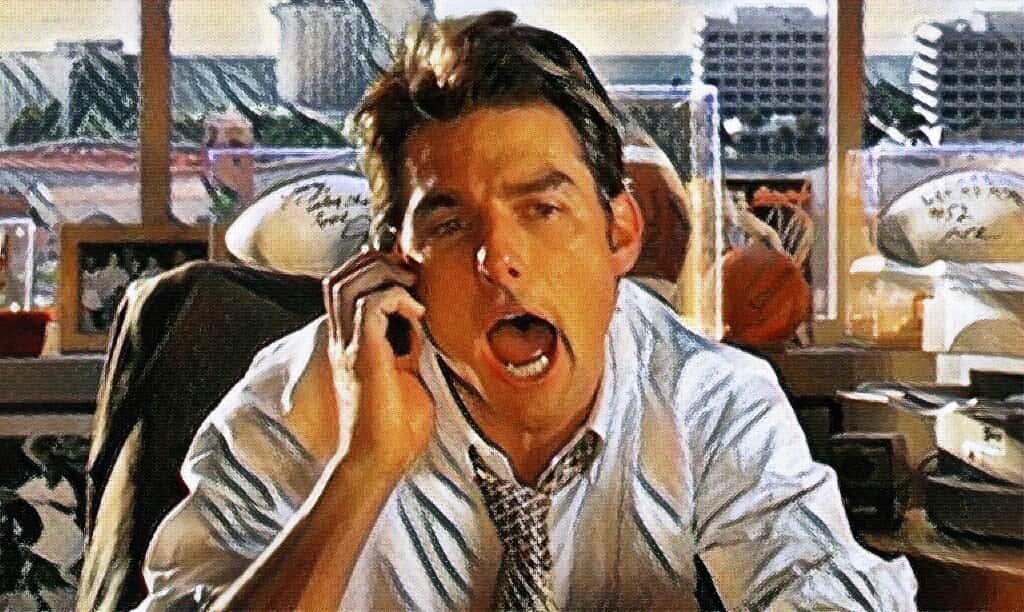

The same year, Cruise went around tugging heartstrings in Jerry Maguire, a sports agent tormented by a conscience—an oxymoron sinfully heavenly, one could only wish its survival in Tinseltown. Cameron Crowe had penned the jewel, and Cruise gave the sort of performance where tough guys would roar into their pitchers, sobbing, “Show me the money!” It opened on a world-earnings spree of a breathtaking $273 million, all on a $50 million investment, which is literally the economic miracle of water into wine, had wine a recipe of sheer moneymaking.

The decade’s deserving finale arrived in a double-bill of cinematic magic which would have made Shakespeare laugh with jealousy. Firstly, there was Eyes Wide Shut, featuring Cruise and Nicole Kidman together under the inspired direction of Stanley Kubrick in what can only be described as the all-time highest-budgeted couples therapy ever put to screen. Peter Bradshaw endorsed Cruise’s reckless candor, discussing the manner in which he “opens himself up in that ferociously committed way.” Translation: the man acted his socks off, sometimes literally.

Then there was Magnolia, supporting performance by Cruise playing motivational speaker Frank T.J. Mackey—an acting performance so completely demented in slow motion that merely watching him felt like witnessing a beautiful car wreck with superior dialogue. According to Peter Travers, Cruise starred as “a revelation” who “seethes with the chaotic energy of a wounded animal.” A second Golden Globe and Oscar nomination followed this self-destructive acting performance, because clearly the Academy would greatly like to be emotionally devastated by Tom Cruise like everyone else.

This fabulous decade had Cruise do a heck of a lot more than act—well, at least, become a coiffed Napoleon with a better smile. He evolved from action star to straight actor with the bravura of a conjurer plucking rabbits from caps, only his rabbits were Oscars and the hat had a lining of box office dough. Being versatile was a mightier force than a Swiss Army knife, praise by critics steadier than gravity, popularity steadier even than death, taxes, and his own impulse to perform ever-riskier stunts.

2000s: The Decade Tom Cruise Convinced Hollywood He Could Actually Act

The 2000s Tom Cruise had risen so high into the stratosphere of the ridiculous that gravity itself was forced to pen an outraged letter to request an attorney. By the time Mission: Impossible 2 arrived in 2000, our little risk-taker didn’t just return—he burst back into our lives like a bike smashing through a plate-glass window of sanity.

Hong Kong slow-motion violencépoet laurate John Woo helmed and converted Ethan Hunt into a motorcycle-licensed suicidal ballet dancer. And the reward? A world-wide box office gross of $547 million, which proved people would gladly bet their houses on the mortgage just in order to see a guy break physics like a gentle hint. Critics descended with all the fervor of stale toast—there were those who went ga-ga on the killing-operatic, and those who felt they’d participated in a cologne advertisement by a guy who has unlimited access to ordnance.

But where sanity took a flying leap over the cliff: its so-called movie fever fantasy, the biggest-grossing film of 2000. Yes, at a time when cinemagoers literally could’ve done anything whatsoever, they all, en masse, said, “You know what’s plausible? Spending all day sitting around watching Tom Cruise dangle from increasingly-precarious heights with the hair on his head supplying structural integrity on a par with a suspension bridge.” “The MTV Movie Awards, arbiters of high culture and moviewatch enjoyment, awarded him Best Male Performance—most likely, result of skill work in causing insurance adjusters to cry unrestrainedly.”

Between M:I-2 and its upcoming sequel, our tireless hero careened through Hollywood like a hyper-coffee-fueled hummingbird on Red Bull. Vanilla Sky showed he could glumly photogenically sit with a face full of starring facial hair. Minority Report ensured flying theatrically cinematically through worlds not yet seen was his one and only passion. The Last Samurai illuminated the more interesting fact that, supposedly, the last samurai was some guy from Syracuse with better dental work. But we’re all enthralled by the Mission: Impossible mayhem, the stunning, gory spectacle of a man fighting a battle with gravity itself.

Then came 2006 and Mission: Impossible III, the movie which posed the biggest question of film: “What if we inflict emotional AND physical agony on Ethan Hunt, ideally dangling him off some REALLY tall thing?”

Curmudgeonly critics, those grumbling guardians of artistic integrity, yes, fell helpless under this one like hypothermic penguins who’ve found a hot tub of liquid love. They referred to it as a “return to form”—i.e., in Mission: Impossible terms, “a wee bit less insane than a fever dream, but insurance companies self-destructing spontaneously during the stunt sequences.”

The movie ran close to $400 million at the box office once again proving the bottomless desire among viewers to sit back and watch Tom Cruise disregard physical law like pesky party guests who refuse to take a hint and depart. Philip Seymour Hoffman emerged onto stage with the bad guy, acting with such masterfully malevolent perfection that the old Mission: Impossible bad guys seemed to have graduated summa cum laude from the Wimp Academy of wannabe baddies.

What’s particularly cool about the evolution of this trilogy is how well it tracks Cruise’s own career arc: from “Behold, I can do stunts!” to “Behold, I can do BIGGER stunts!” to “Behold, I can do IMPOSSIBLY large stunts and express actual human feelings doing it!” It’s like seeing someone catch on, oh wait, yes, humans would prefer it more if there was some character growth in the midst of all the explosions and motorcycle chases bending a few basic laws of the universe.

The reviews are a slow-burning romance book: initial skepticism, creeping fondness, and then, begrudging respect on the edge of Stockholm syndrome. Writers were swayed to liking that grumbling about realism in a Mission: Impossible movie is like grumbling that unicorns aren’t properly filling out their tax returns—you’re hugely missing the point, yeah?

Orbiting around him is Cruise, all megaward and draped on increasingly higher and more ludicrously implausible wires, brazenly yelling into the far reaches of space, “Physics? Wherever we’re going, we don’t need no stinking physics.” This chap has resurrected career suicide half-a-dozen times, he’s pretty much the Lazarus of impossible stunt activity—better hair, better smile, naturally.

2010s: Action movie roles

2010s were Tom Cruise’s wild-eyed craziness—year when Tinseltown’s all-time biggest brain taught physics to his own arch-nemesis and box office projections a joke 述. Buckle up, folks, because our trainwreck is in gear.

Knight and Day arrived in 2010, and even Cruise’s otherworldly charm couldn’t resuscitate Cameron Diaz’s career from its cozy obscurity. That abomination of an action-comedy was treated by critics like toxic waste, and willing ticket-buying patrons sent their cash on literally anything but. Knight and Day sported a death certificate coming.

Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol arrived in the guise of a vault of muscle hand-delivered by its star, Cruise, all folding down from the Burj Khalifa and scowling at gravity. Critics wrote sonnets of love on paper, people took lifetimes, and $694 million later, we all recalled why we adored the impossible man. Suddenly, watching Cruise almost die on one of our entertainment’s controls felt a cause of personal religious zeal.

As a bonus scene-deserving twist, Rock of Ages in 2012 turned Cruise into Stacee Jaxx, rock sensation with a MORE eyeliner dependency than even the biggest fake of a goth would ever permit. Rock of Ages tanked bigger than a heavy metal drummer on crystal meth, but there’s no possibility of critics not adoring Cruise’s commitment to be completely insane. Disaster, every once in a while, is a sweeter flavor.

Winter arrived in December during the biggest casting fiasco of the century. People went berserk like irate volcanos—5’7″ Cruise can’t be a 6’5″ giant? But the film walked past $217 million worldwide, and why? Height difference is blissfully overlooked by the masses once you spin people around with enough artful élan.

Oblivion (2013) were all the accoutrements of liquid attractiveness layered on top of a committee screenplay. Morgan Freeman starred because there is a science fiction film rulebook that doth insist all-powerful Morgan’s voice talk directly to all of us, and Olga Kurylenko delivered the Beautiful-but-Aloof monologue. Critics stared at attractive visages and tiptoed delicately around yawning holes large enough to float ships through.

And then there was Edge of Tomorrow, a “Groundhog Day” on steroids and rage. Kill Tom Cruise again and again and do better—a notion so wonderful it must be on lists of must-see film school fare. Critics were infatuated, audiences lost their minds, and $370 million and some spare change down the road, everyone concurred that killing Cruise ad infinitum is good cinema.

Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation began in 2015 as an old habit. Jeremy Renner and Simon Pegg carried on their sideline Cruise-watch work too, because our hero had once again violated the laws of physics and sanity. Critics had long given up on resigning themselves to the perfection of the formula—complaining about Mission: Impossible would be criticizing chocolate for containing too much chocolate.

The Mummy (2017) surfaced on our screens as a Universal Dark Universe franchise, only to initially die in a spectacular dumpster fire. As Cruise flips between pirate ships and a budget on which one can purchase small nations, critics shredded it apart like rabid dogs. Yet even this blockbuster failure cost a whopping $400 million—because terrible Tom Cruise movies still make more than most thespians’ masterworks. The Dark Universe died in its teenage years, with nothing but costly wreckage left behind.

Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018) appeared like the best endman—or literally hanging suspended in mid-air off helicopters because, goodness sakes sake, quitters walk. Critics were left agog, the public threw wallets wide in loyal fandom, and $791 million later, Cruise harvested the top-grossing film of his lifetime. Perfection does in fact hang, literally, from airplanes.

The decadent decade’s handling of Cruise has been a caffeine-infused maniac roller coaster—angry, remorseless, now thrilling. Do not pass Go, Mission: Impossible? Pundits fawn like groupies who just collided with their icons. Witness something different? Reaction has varied from “charmingly insane” to “what the freak is this?”

This is honeyed craziness: even Cruise flops gross higher box office numbers than other people’s hits. This crazy masterman can probably spew grocery lists into a tape recorder and perform death-defying feats, and the thing would be a success at $200 million. Tom Cruise is not the king of crazyhouse Hollywood insane asylum – he’s the entire royal family on a throne of crown jewels built out of box office profit and critical bewilderment.